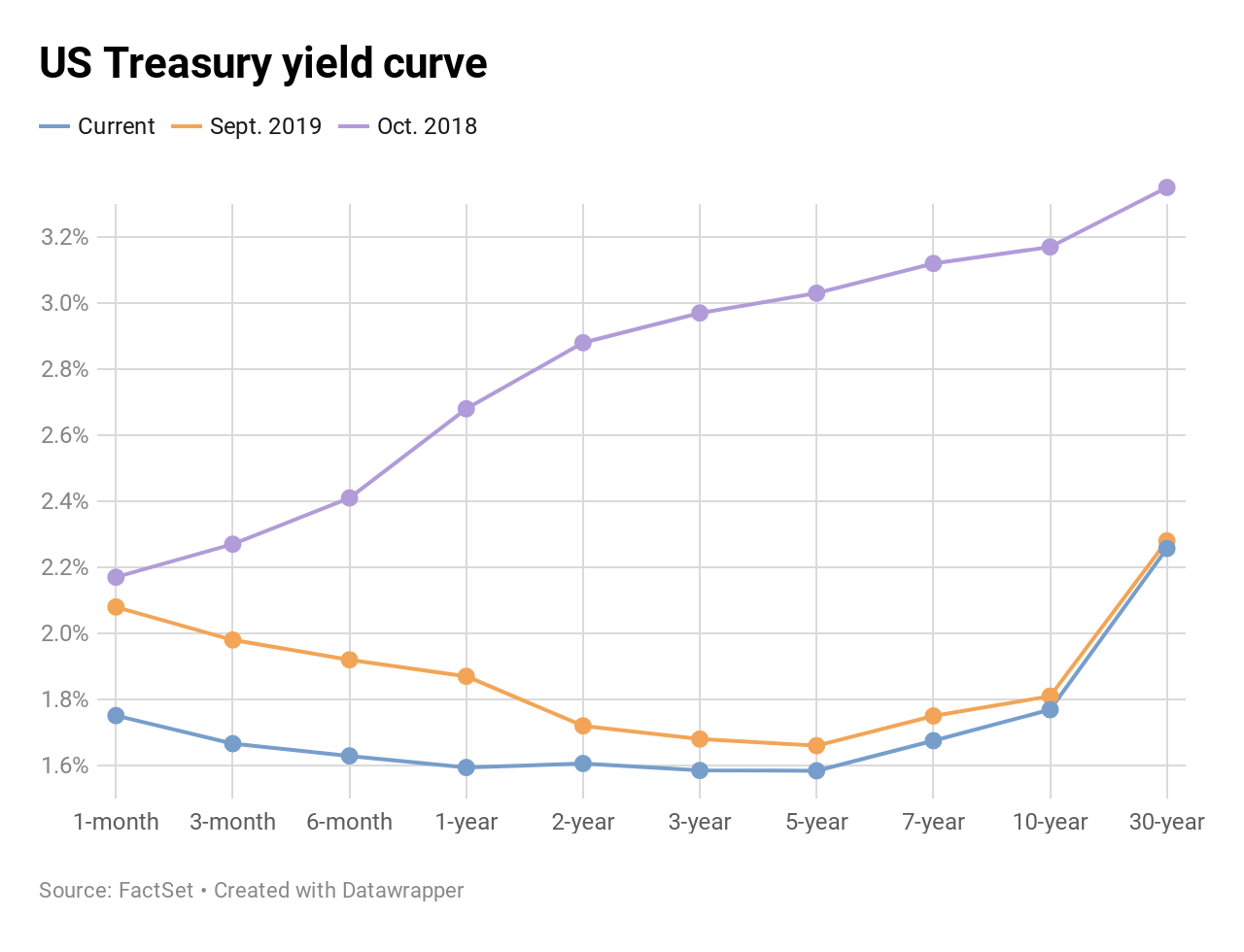

The frightful bond-market phenomenon that saw the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury fall below that on the 2-year rate, triggering recession fears on Wall Street and Main Street, has reversed itself.

But you may want to hold off on the Dom Perignon and party hats.

A sudden steepening of the curve following an inversion like the one occurring now almost always happens just before or during U.S. recessions.

A pessimistic interpretation of the recent economic tea leaves could include the Federal Reserve, seeing signs of an impending slowdown, started cutting short-term interest rates because officials believe the economy is set for a deceleration.

"What people don't understand is that when the recession is getting to be close to your doorstep, the curve actually steepens out because the Fed gets the joke, finally, that they're behind the curve and they need to cut interest rates more," longtime fixed-income investor and so-called "Bond King" Jeffrey Gundlach said last month in an interview with CNBC.

"The way history has kind of proved to work is that when the curve inverts for the first time ... what happens historically is the curve inverts well before a recession," he added.

The Fed began cutting rates in July. It cut again in September.

.1571399901166.png)

The U.S. bond market is almost always more stable — if not outright boring — compared to the dramatic and volatile stock market. Treasury yields can remain range-bound for months at a time, interrupted only by fluctuations of a few fractions of a percentage point.

So when the yield on the 10-year Treasury note earlier this year fell at a breakneck speed from 2.75% to 1.6% over six months, it triggered a host of alarms across Wall Street. The plunge was so severe that it sent the yield on the 10-year note under that of both the 3-month bill and 2-year note, a rare phenomenon known as "inversion."

Though the inversion between the 10-year and 2-year proved short-lived, the yield on the 3-month bill held above the 10-year for months. The spread widened into positive territory earlier in October for the first time since July.

Investors usually demand higher interest payments for agreeing to lend Uncle Sam money over longer time periods, so deviations from the status quo are thought to be reliable, though not perfect, recession predictors. Still, analysis shows there is often a significant lag before a recession hits and an economic downturn ensues.

For example, the last inversion of the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields occurred in December 2005, two years before the financial crisis and subsequent recession.

.1571404285269.png)

Data from Credit Suisse going back to 1978 shows:

- The last five 2-10 inversions have eventually led to recessions.

- A recession occurs, on average, 22 months following a 2-10 inversion.

- It's not until about 18 months after an inversion when the stock market usually turns and posts negative returns.

It was little surprise, therefore, to hear President Donald Trump's top economic advisor, Larry Kudlow, tell CNBC on Thursday that he was happy to see the spread between the 10-year and 2-year back in positive territory, albeit at a flattish 15 basis points.

"Here's the good news: The yield curve – 10s versus bills, 10s versus 2s – has now finally moved back into a normal position," Kudlow said from the White House lawn. "Long rates are now above short rates. Not by a lot, but by some. That's a good sign."

But an un-inverted yield curve isn't necessarily a reason to celebrate, either, Martin Enlund and Andreas Larsen of Nordea Markets told clients in a note published Friday.

"While a steeper curve may be regarded as reflationary (growth returning, inflation picking up etc), steepening can also be a worrisome sign," the two strategists wrote. "Looking at the inversions of the US curve since 1978, a re-steepening (un-inverting) of the curve seems to occur during (1980, 1981) or preceding US recessions (1990, 2001, 2007)."

"Indeed, over the past 40 years, only during the successful precautionary rate cuts in 1998 did a re-steepened yield curve not constitute a worrisome sign," Enlund and Larsen wrote in their Friday note.

To be sure, while recessions are almost always preceded by a steepening of the yield curve, not every instance of yield curve steepening leads to an economic downturn.

The recent rise in the 10-year Treasury yield could also be explained by an improved outlook in real GDP, Leslie Falconio, UBS Global Wealth Management senior strategist, said in a note earlier this week.

"It may be too soon to make the call that the yield curve is now on a path toward steepening. However, there is no question that the recent progress in the US/China trade talks have pushed US 10-year yields higher," she wrote.

Other economists have suggested that the possibility of a Brexit deal between the United Kingdom and the European Union has bolstered the global GDP outlook.

Still, while Falconio conceded that the Fed's recent purchases of U.S. bills has steepened the curve, she did not go so far as to tie its buying to a belief in a forthcoming recession.

"The shape of the curve continues to remain on the radar of the Fed," she wrote. "One reason for them to buy short end Treasuries versus an even dispersion along the maturity spectrum, is to influence the shape of the curve."

But whether the Fed's recent cuts and bond purchases reflect mere tweaks to an otherwise healthier economy as Falconio might suggest or a safeguard from something more sinister as described by Gundlach remains to be seen.

Reaed More

Post a Comment