Demonstrators gather outside Houses of Parliament for a protest on 03 September, 2019 in London, England to oppose the prorogation of the U.K. Parliament.

NurPhoto | NurPhoto | Getty Images

With the U.K Parliament now shuttered for five weeks and the recent political turmoil throwing up more questions than answers, analysts have been busy contemplating what could happen next in Britain as it approaches its Brexit deadline.

The shutdown of Parliament — known as prorogation — will see lawmakers reconvene on October 14. The suspension marks the end of one parliamentary session before the start of the next, and it's usual for it to take place at this time of year.

However, the current shutdown, which began in the early hours of Tuesday, is more controversial than most due to its extended length and because it comes at a period of high anxiety in U.K. politics over the direction of Brexit.

It's fair to say the U.K.'s political establishment has been in tumult since the divisive 2016 referendum on EU membership. It has culminated in Parliament's three-time rejection of the existing Brexit deal on offer, but also the dismissal of a no-deal Brexit.

This summer, Parliament saw the arrival of a new prime minister in July determined for the U.K. to leave the EU on October 31 "come what may."

What just happened?

That divide between Prime Minister Boris Johnson's government and Parliament was thrown into sharp relief in a dramatic week full of intrigue, votes and resignations.

In the last seven days, lawmakers seized control of parliamentary business, voted to block a no-deal Brexit and to force the prime minister to ask for a further delay to the departure (legislation that hastily became law on Monday) as well as twice rejecting Boris Johnson's bid to bring about a snap election that could strengthen his hand.

Johnson was dealt further blows with key resignations from his government, including that of his own brother who said he was torn between "family loyalty and national interest."

Now Parliament is suspended for five weeks and will reconvene just days before an EU Council summit on October 17 which is just over two weeks from the currently proposed Brexit departure date.

Here's a brief guide to what could (and what is meant to) happen next:

Brexit on October 31?

As it stands, the U.K. is still due to leave the EU on October 31 whether it has a deal or not. A majority of Parliament voting to block a no-deal Brexit does not mean that it won't still happen.

For starters, the EU would have to agree to granting another delay to the U.K.; and there are already grumblings from the continent that the U.K. has not presented valid reasons for requesting more time. Johnson could also ignore the law requiring him to ask for more time.

Ignoring a no-deal Brexit

Despite Parliament voting to block a no-deal Brexit and passing a law, Johnson has repeatedly said he would still try to take the U.K. out the EU on October 31.

In fact, he has said he would rather "die in a ditch" than ask the EU for more time and some believe he could launch a legal challenge to the no-deal Brexit legislation, also known as the "Benn Law."

"Johnson is expected to challenge the Benn Law in the Supreme Court," analysts Joseph Lupton and Olya Borichevska at J.P. Morgan said in a note Monday.

"He also may send a letter to the EU to encourage it not to grant an extension. Those strategies are unlikely to succeed on their own merits, but could further Johnson's pre-election signalling of a hard-line, no compromise Brexit on October 31."

More talks?

Johnson has insisted he wants a deal and would use the time that Parliament is suspended to continue last-ditch talks with Brussels to get over the major stumbling point of the Irish "backstop."

This is seen as an insurance policy designed to prevent a hard border on the island of Ireland if the U.K. and EU can't agree a trade deal in a post-Brexit transition period (only envisaged if there is a deal). As it stands, the backstop would keep Northern Ireland and the rest of the U.K. in a customs union with the EU, making it very unpopular with Brexiteers in Parliament.

The BBC reported Monday that the government could be considering a compromise over the Irish "backstop" in that it could be applicable to Northern Ireland only, potentially placating Brexiteers — albeit at the expense of lawmakers bent on keeping the U.K. indivisible in terms of law.

Election before 2020?

Although opposition parties defeated Johnson's bids to hold an early election (his Conservative Party still leads opinion polls) most did so because they wanted to see the threat of a no-deal Brexit dissipate.

The legislation to block a no-deal Brexit was not enough for many lawmakers, however, with several opposition parties wanting to see the departure date delayed before agreeing to a snap election (Johnson needs two-thirds of Parliament to approve a snap vote).

With Parliament also suspended now until October 14 and the no-deal Brexit legislation in place, most Brexit watchers now see a snap election as likely to happen in November, after a possible delay to the departure date.

How the pro-Brexit Conservatives and Brexit Party will fare, compared to opposition parties largely opposing Brexit or at least calling for another referendum on the issue, is now a matter of debate.

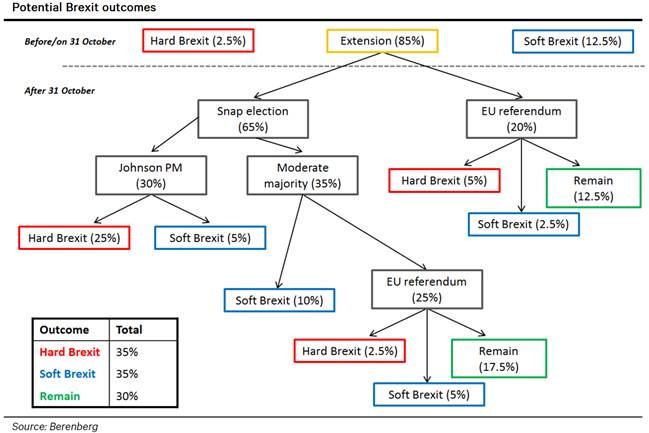

Kallum Pickering, senior economist at Berenberg Bank, said in a note Tuesday that "the prospect of an election and/or second referendum looms large," forecasting an election in November.

"Despite the turmoil in Westminster, the high chance that the U.K. will ask the EU for a further Brexit delay (given a probability of 85% up from 40%) decisively reduces the risk of a no deal on 31 October (2.5% from 30%). However, the prospect of an election and/or second referendum looms large — this keeps the hard Brexit risk alive."

Deal by October 31?

With speculation that Johnson's government could be considering the proposal of a compromise over the "backstop" policy, some experts believe that a deal could still possibly be passed before October 19.

Goldman Sachs' base case scenario says "there is no pre-Brexit general election and a Brexit deal is struck and ratified by the end of October," according to its European Economist Adrian Paul.

"In substance, we think that deal is unlikely to look very different from the Brexit deal already negotiated between the EU and the U.K. — a deal that was repeatedly rejected under PM May's premiership."

Still, Goldman Sachs notes that a delayed departure could lead to a November election in which either the one-issue Brexit Party could do well leaving "the path open to a 'no deal' Brexit early next year."

Second referendum?

Alternatively, opposition parties could unite to try to bring about a second referendum. "The potential for the Liberal Democrats or the SNP (Scottish National Party) to accrue influence in a minority government led by the Labour Party after a November general election preserves a path to a second referendum," the Goldman analysts noted.

Goldman has revised down the probability on a "no-deal" Brexit from 25% to 20% and the probability of "no Brexit" from 30% to 25%.

Reaed More

Post a Comment